Wolverton Castle & Medieval Village

The buried remains of the Norman motte and bailey castle and earthworks of a medieval village can be found at Old Wolverton.

The earthworks at Old Wolverton village lie under the green areas of Manor Farm Court in the East and Holy Trinity Church in the West of Ouse Valley Park, now divided by the canal. Today you will often see sheep and cattle grazing here.

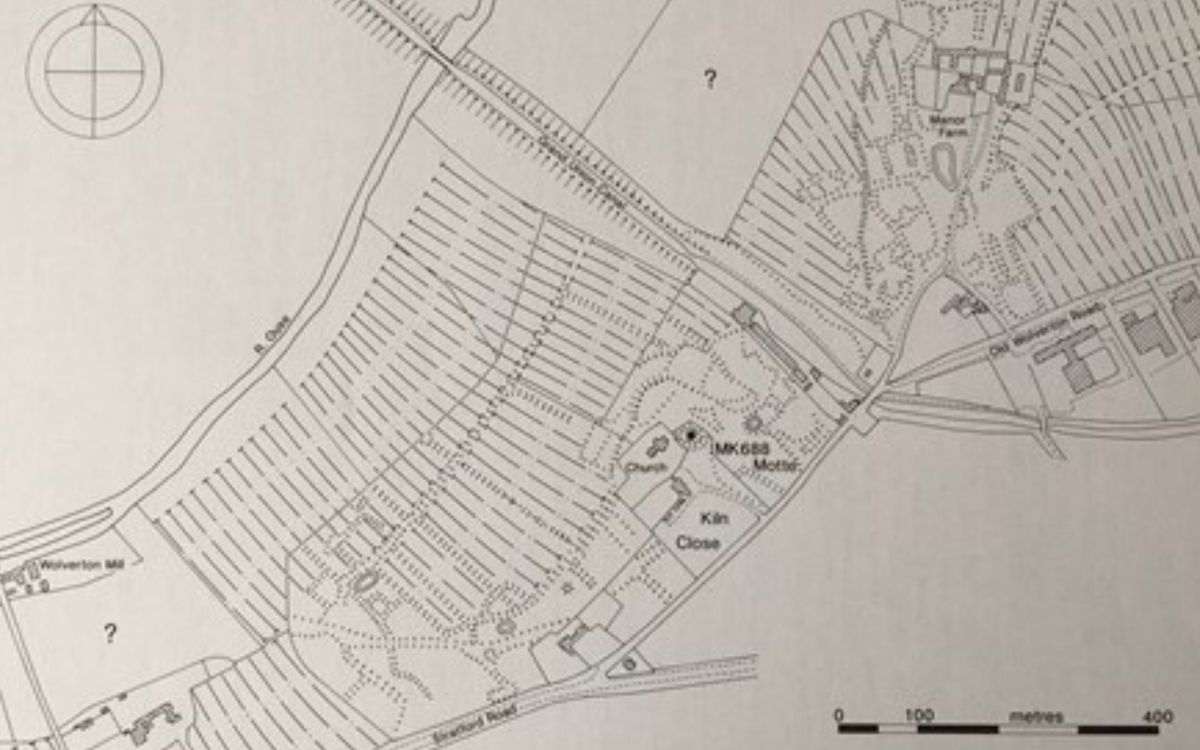

The map shows the extensive earthworks on site. The Norman Motte and Bailey castle lies to the east of the church on the higher ground. The deserted medieval village survives as extensive earthworks within which roadways, boundaries and house outlines can be seen.

This is such a special site that it has been listed as a Scheduled Ancient Monument and is protected by law.

What can you see at the east of the village, at Manor Farm?

The early 19th century Manor Farm farmhouse is a rebuilding of an earlier 17th or 18th century house, and its farm buildings are thought to be built on top of the remains of a medieval grange – a farm run by Monks. The Gilbertine Order ran this particular grange. The ‘lay brothers’ of the order farmed the land, producing crops, raising livestock and possibly also producing beer to sell. This provided an income for their Priory at Clattercote in Oxfordshire.

Ownership transferred to another Priory (Chicksand, Beds.) before being sold to a London merchant in the 1300s. The land then became part of the Longville manor in the Tudor Period.

Archaeologists who excavated Milton Keynes believe it to be the best example of deserted village in Milton Keynes (Croft and Mynard). You can still see most of the street that ran from Wolverton Mill in the west to Manor Farm in the east (the main track up to the house). The numerous former quarry pits and well-defined crofts suggest the footings of the village were constructed of limestone. The peasant houses would probably have had a stone base and then been built up using wattle and daub.

At least one croft is visible to the east of the track, while you can identify five or more on the west. The oval pond is also believed to have been there at the time, providing water for livestock. To its east is an open triangular area that may have been a village green. There is a sunken road to the back of the crofts, and signs of ridge and furrow – a land form that was created by traditional methods of ploughing (see below).

You can see more evidence of ridge and furrow in the fields to the back of the farm buildings, towards Floodplain Forest. Don’t be fooled by the dips in these fields. They are not earthworks of the village but were probably created by people quarrying for stone during and after the medieval period.

There is written evidence to suggest that a watermill (known as ‘Tirle Mill’) was still here in the 1700s, situated at the bottom the field (‘Grange Field’) to the north of Manor Farm. The river would have powered the mill, turning the large millstone to grind grain into flour. Although no trace of the mill buildings survives, a fragment of gritstone millstone was found close to the site in 1979.

Built before the railway and the car, canals revolutionised transport, allowing heavy goods such as coal to be pulled by horses over water. This part of the Grand Union canal (then named the Grand Junction) was finished in 1800, linking Birmingham to London. The famous Iron Trunk Aqueduct is nearby, carrying the canal over the River Great Ouse.

What can you see in the western part of the village, by Trinity Church?

You can still see the remnants of the early Norman castle. The motte, the mound of earth where a wooden keep would have stood, is now covered with trees and surrounded by a fence by Trinity Church. It measures 50 metres in diameter at its base, and 20 metres at the top. Although only 5 metres higher than the churchyard, it was 78 meters above sea level, and commanded a great view of the Ouse Valley below. The wooden keep was the safest place in the castle.

The bailey is at the base of the motte, an area of land that would have contained a few buildings and been surrounded by a wooden fence. You can just about trace the edges of the bailey which has been pockmarked by small quarry pits. Both the motte and bailey would have had a ditch around them – the north side of the 6 metre ditch around the motte still exists (it now contains a limestone wall).

Castles were built for defence and as a sign of power. The manor (the land) of Wolverton was granted to Manno le Breton by William the Conqueror for his support after the invasion in 1066. This kept his best fighters onside and helped William to control the land. However, while many motte and bailey castles were built during this early period, it is believed that it was probably Manno’s son, Meinfelin or his grandson, Hamo, who built the castle at Wolverton, in the late 1000’s or early 1100’s. Most likely it was built during the Anarchy – a time of civil war when Stephen and Mathilda were fighting for the crown.

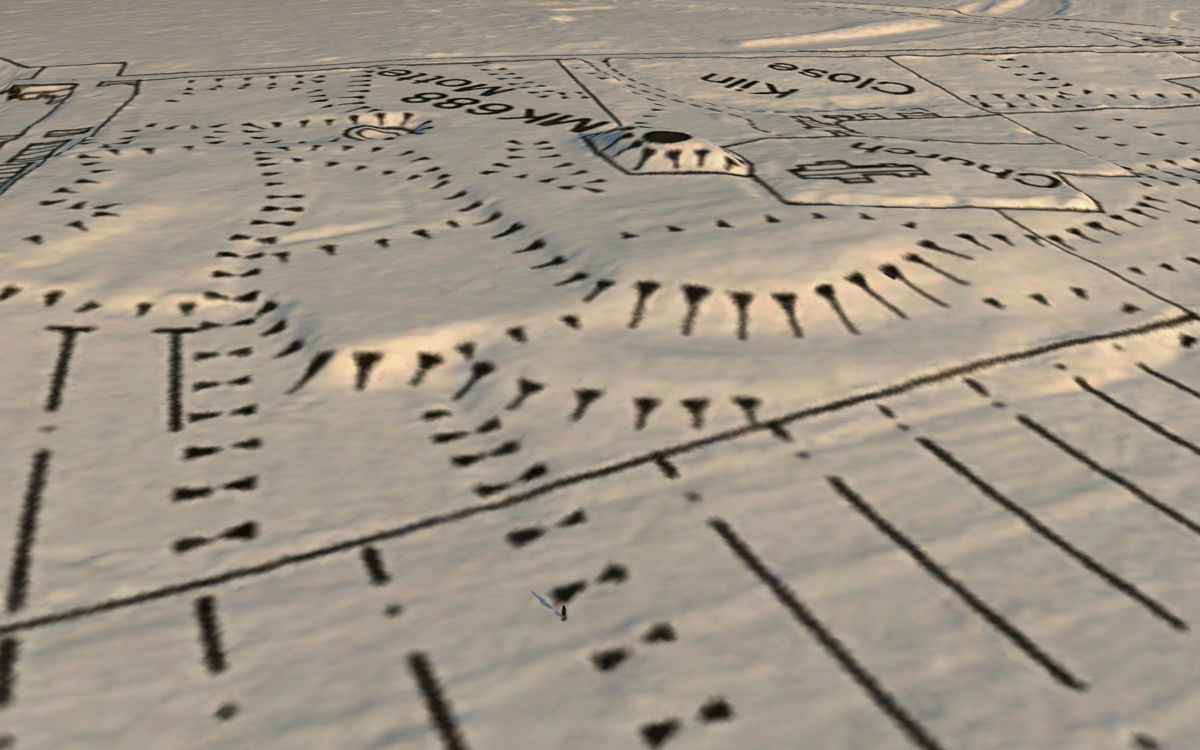

The high elevation, as shown by the lidar image, would have helped its defenders see people approaching and helped protect the site.

On this site, you can see the centre of the manor which would have had a manor house, demesne (the area of land around the manor house), the village street, a church (now replaced by the Victorian Holy Trinity), woodland for collecting firewood and timber for building, fields for farming and common land where peasants could graze animals and collect resources.

Archaeologists who excavated Milton Keynes believe it to be the best example of a deserted village in the New Town (Croft and Mynard). You can still see most of the street that ran from Wolverton Mill in the east to Manor Farm in the west (then known as the Grange). In the fields below Holy Trinity, the street runs under the more modern walled garden and houses and then emerges as a sunken track that bends towards Wolverton Mill. With thanks to the Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society for sharing the image from Croft and Mynard, The Changing Landscape of Milton Keynes, 1993.

You can also make out the back lane that joins the main track. On either side of the street you can see the earthworks of farm crofts (small fenced areas that peasants would have used for growing extra vegetables or keeping animals), many of which have platforms where a peasant house would have stood. The sunken track and well-defined crofts suggest the footings of the village were constructed of limestone. The peasant houses would probably have had a stone base and then been built up using a timber frame or “cruck” with wattle and daub infill. Behind the back lane, there are banked areas surrounding ridge and furrow (created by years of ploughing). The Earth banks around these closes may have been banked to protect them from flooding.

The manor house itself no longer exists. No records survive about the Norman manor and the manor built by the Longville family in the 16th century fell into disrepair and was demolished by the Radcliffe Trustees in 1725. This was thought to be south of the motte, north east of the driveway, in front of the rectory (Longueville Court). The rectory was built in 1730 using the stonework from the demolished house. If you look (discreetly) at the surround of the rectory door you can see part of the 16th century stonework.

Who lived here?

After the invasion, William commissioned a “Great Survey” recorded in the Domesday Book (or, more accurately, books) to find out how much land and wealth he controlled, and to help him tax people in the future. This document tells us that the village was made up of 50 households in 1086, with an estimated population of 250. This is relatively large for the period - in the top 20% of settlements listed in the Domesday Book.

While we know little about the peasants who lived here, we know far more about the owners of the Manor - the Barons of Wolverton, as the descendants of Meinfelin were named after the 1200s. Sir Frank Markham, the eminent local historian, dismisses the family as ‘a feeble lot’ who achieved little. We cannot judge the accuracy of this statement as Markham appears to base this mainly on the lack of military achievement and production of legitimate heirs. However, the male line stopped before 1360 and a female descendent married John de Longville. The Longville family continued to hold the estate for centuries until the Radcliffe Trust acquired it in the 1700s. John Radcliffe had been a physician (doctor) to the monarchy and owned part of Stony Stratford, the manor here, and Stacey Hill Farm (where Milton Keynes Museum is today).

What happened to the village?

The village is thought to have been deserted by the 1580s. It is unclear whether plagues reduced village numbers – the Black Death in 1348 had led to the abandonment of many villages in England and plague continued to strike intermittently. Enclosure would certainly have had a role here. The Longville’s gradually fenced off land, including the common land that was often crucial to peasants’ survival. This could have been partly to rear sheep which was a very lucrative business in the Tudor period. The change to sheep farming also required fewer peasants, meaning that many lost their income and could not pay rent for their land holdings or were simply forced off the land by the Landlord. By the 17th Century, the Longvilles had enclosed the whole area to serve as a park for the manor, probably to breed deer for hunting. The fields that had once been a village were originally named - Lower Park and High Park.

Where can I find out more?

Milton Keynes is one of the most studied archaeological landscapes in the UK and there are lots of other heritage sites in The Parks Trust parks and elsewhere in the city. To find out more about this site, or the many others, look below.

- Domesday Book - see images of the records for Wolverton

- Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society - provides talks and more information on historic sites across MK

- Milton Keynes Museum - where artefacts are stored and the history of MK can be explored

- View Historic England Listing

The remains of the Wolverton Castle and Medieval village can be found in the Ouse Valley Park. This linear park is a fantastic place for a peaceful adventure taking in the abundance of wildlife and checking out the heritage sites.

There are multiple free car parks available.

Discover Milton Keynes' heritage by exploring the city's historical landmarks and scheduled ancient monuments.